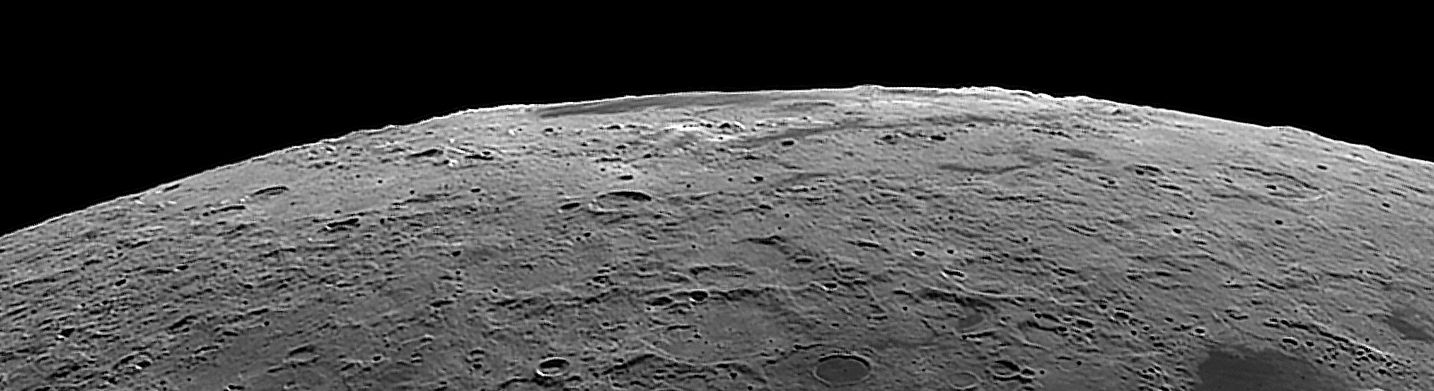

Orientale is the best example of a multi-ring basin on the Moon. Unfortunately it is situated almost entirely on the far side of the Moon, as defined by the 90°W longitude line which just skirts the eastern edge of Mare Orientale. Consequently it only becomes visible from Earth when the libration is particularly favourable.

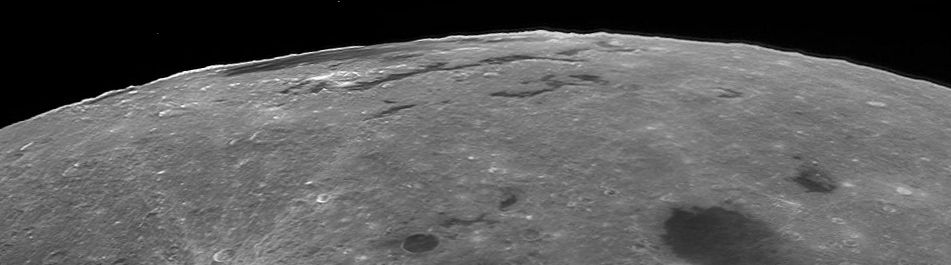

It is almost impossible, in any image of this area taken from Earth, to see the multi-ring nature of the basin. Although the Cordillera and the Rook Mountains have been known for a long time, their nature as part of a multi-ring basin was not known until Bill Hartman, working on the Rectified Lunar Atlas in Gerard Kuiper's Lunar & Planetary Laboratory in 1961, discovered it by projecting high-quality photographs onto a 3-foot diameter, white sphere and rephotographing them from "overhead". Indeed neither mountain range is at all obvious in any of my photographs of this area (so far, anyway!), except where they pass over the limb. I have indicated these places in the mouseover of the image above. The Cordilleras start on the right of the image where you can see a distinct bump on the limb, pass just this side of Lacus Autumni, through Eischstadt and Shaler before disappearing over the limb about where indicated. The Outer Rook Mountains start, again, with a bump on the limb, pass just this side of Lacus Veris, carry on round to pass over the limb with another bump where indicated. The Inner Rook Mountains are best seen as they skirt along the limb on the far side of Mare Orientale and closely encircle the mare. What can be clearly seen is the remarkably flat area between the Outer Rooks and the Cordilleras, particularly on the left and right (south and north) sides of my picture. These flat areas can also be seen on the overhead picture shown below. The two lakes, Veris and Autumni (Spring and Autumn) fall between the rings (just inside the Outer Rook and Cordillera mountains respectively) as, I suppose, one might expect.

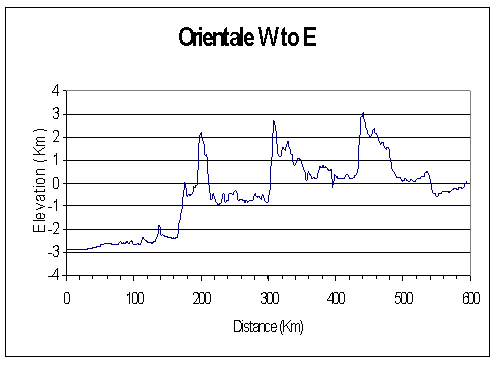

Photographing the libration zones, especially areas such as this in the East or West, is particularly difficult because somehow the lighting is never right. When this area first comes into view just after Full Moon, the Sun is low in the sky of Orientale, so there are plenty of shadows. However, the shadows are all behind the objects producing them, and the area shows the same bland nature typical of the Full Moon. This remains true as the Sun rises over Orientale and the phase moves towards last quarter. At that point, the Sun is almost overhead at Orientale and so there are no shadows to see. As the Sun moves further west in the lunar sky, shadows reappear coming towards the camera, but the mountains tend to disappear because the Sun is lighting their far side and the nearer side is in darkness. Add to this the fact that the libration is only favourable once every lunar month and this may not correspond to a desirable phase, and you can see that the opportunities for good photographs are few and far between. In the particular case of the Orientale Basin, the problem of lighting is illustrated by the two pictures below which are rearranged copies of the first and last pictures on my previous page. When the upper picture was taken, the sunset terminator was at 3.5° west so the Sun was on the lunar meridian very near the centre of Mare Orientale which is at longitude 95° west. M. Orientale is at latitude 20° south and the Sun was about 1° north of the lunar equator, so was at an altitude of about 69° in the northern sky. The maximum easterly point on the Cordillera mountains is only 15° east of M. Orientale so the Sun will still have been very high in the sky. In the second picture, the sunset terminator had moved on to 53° west and the Sun had move another ½° further north, so the Sun was about 27° above the western horizon at the Cordilleras. You might think that this is low enough to produce nice shadows and to leave mountains unilluminated. However, the slope on the eastern side of the Cordillera mountains is quite gentle; the graph above is quite deceptive because of the difference in scale between the two axes, but if I had made them the same the graph would have been almost flat. Looking at the eastern slope of the Cordilleras on that graph you can see that the ground drops about 4 Km in a distance of 100 Km, an average slope of 0.04 or about 2.3°. Obviously there will be parts steeper than the average which may produce shadows but these are likely to be small. You can see shadows inside some of the craters, Eischstadt and Wright for example, where the slopes are somewhat steeper. And there are what look like shadow-filled craters close to Lacus Veris which are probably on the nearer side of the Outer Rook mountains. At the bottom of this picture the Sun's altitude was down to about 15° which produces significant shadows and the rugged nature of this area shows up nicely. Compare this with the upper picture where the altitude of the Sun there was about 40° above the western horizon and there are too few shadows to bring out the topography. However, as with the Full Moon, the dark areas, the maria and the laci, show up nicely.

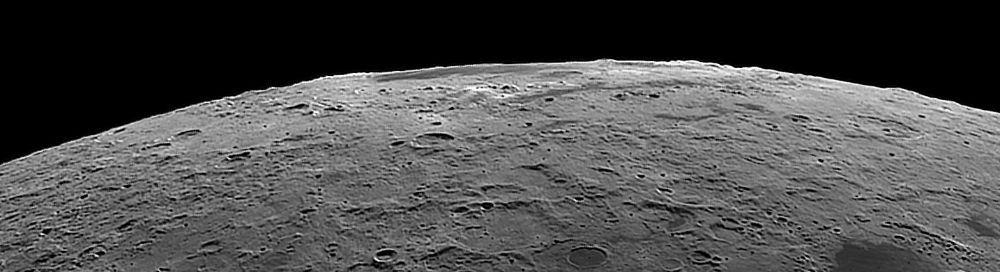

Below is the full-sized image from 13th October 2020.

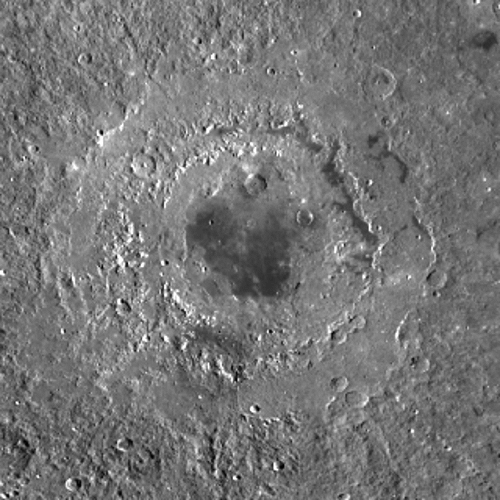

The Orientale Basin seen from above by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. North is at the top and west to the left. Move your mouse over the picture to see, approximately, where the rings are; the innermost ring is unnamed and somewhat doubtful.

A plot of the elevation of the surface west to east from the centre of Mare Orientale eastwards. Note the big difference in scale between the two axes.

Home Return to The Moon